Minimum Wage

Those who decry entitlements and a "welfare state" would be wise to consider the fact that without a living wage, people have no choice but to rely on the safety net of food stamps and public assistance. We cannot at the same time keep people in poverty by denying them a reasonable minimum wage and complaining about their dependency on the government for support.

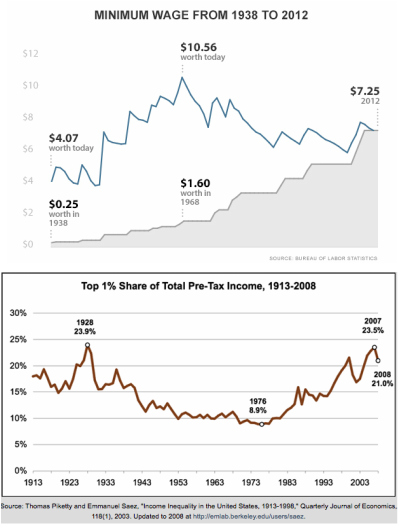

As a young person, I had the opportunity to travel to South America and Africa where I was able to personally witness the consequences for a society that suffered from the absence of a middle class. In Brazil, for example, I saw urban conditions in 1965 far more egregious than any slums in American cities. As a college student, I studied peasant societies and third world development, learning how the rural exodus and shift from an agrarian to industrial economies contributed to poverty, disease, hunger and hopelessness. What I see today in our rising income inequality worries me that instead of expanding our middle class and ending poverty, America has begun to resemble poorer nations. Any serious study or discussion of the gap in income inequality must necessarily consider a wide range of contributing factors: gender, age, ethnicity, education, mobility, labor unions, crime, demographic differences, health and more. Nevertheless, we cannot ignore government's role and responsibility for the favorable trend between 1928-1976 and the reversal of that trend in the four decades since 1976, the same period when the value of the minimum wage has sharply declined and its purchasing power almost vanished completely.

I oppose all specious arguments that a higher minimum wage will cause inflation and shrinking profits, especially when the corporations making these arguments have a greater compensation gap between their executive ranks and workers than at any time in history. I favor an increase in the federal minimum wage will co-sponsor legislation to enact it if I am elected.

Those who decry entitlements and a "welfare state" would be wise to consider the fact that without a living wage, people have no choice but to rely on the safety net of food stamps and public assistance. We cannot at the same time keep people in poverty by denying them a reasonable minimum wage and complaining about their dependency on the government for support.

As a young person, I had the opportunity to travel to South America and Africa where I was able to personally witness the consequences for a society that suffered from the absence of a middle class. In Brazil, for example, I saw urban conditions in 1965 far more egregious than any slums in American cities. As a college student, I studied peasant societies and third world development, learning how the rural exodus and shift from an agrarian to industrial economies contributed to poverty, disease, hunger and hopelessness. What I see today in our rising income inequality worries me that instead of expanding our middle class and ending poverty, America has begun to resemble poorer nations. Any serious study or discussion of the gap in income inequality must necessarily consider a wide range of contributing factors: gender, age, ethnicity, education, mobility, labor unions, crime, demographic differences, health and more. Nevertheless, we cannot ignore government's role and responsibility for the favorable trend between 1928-1976 and the reversal of that trend in the four decades since 1976, the same period when the value of the minimum wage has sharply declined and its purchasing power almost vanished completely.

I oppose all specious arguments that a higher minimum wage will cause inflation and shrinking profits, especially when the corporations making these arguments have a greater compensation gap between their executive ranks and workers than at any time in history. I favor an increase in the federal minimum wage will co-sponsor legislation to enact it if I am elected.